The protagonist in this account jumped on to a trampoline – which he later contended to be a defective product – at his sister’s residence in Brisbane on on Christmas Day 2017.

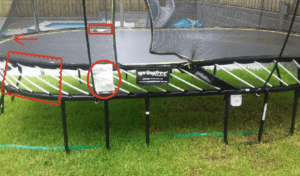

After just a few jumps, he landed near the edge of the trampoline mat on a strip of webbing that housed cleats forming part of the structure’s suspension system.

The impact which he described as “hard” caused his right ankle to roll inwards to cause an inversion injury – also known as a “dancer’s fracture” – involving a fracture of the fifth metatarsal. The injury is commonly seen in athletes and is known to occur on a trampoline.

The impact which he described as “hard” caused his right ankle to roll inwards to cause an inversion injury – also known as a “dancer’s fracture” – involving a fracture of the fifth metatarsal. The injury is commonly seen in athletes and is known to occur on a trampoline.

An experienced trampoliner, Phillip Forostenko believed the trampoline – which used rod-based suspension rather than the traditional springs – to be suspect because of the hard patches in its surface like that on which his right foot had landed.

He decided to sue the device’s manufacturer Springfree Trampoline Australia Pty Ltd for the consequences of his injuries including loss of income in his profession as a physiotherapist for its failure to warn of the safety defect.

The contest for compensation came before Justice Melanie Hindman in Brisbane’s Supreme Court.

She found that the trampoline suffered from a defect in that the cleat design created an increased risk of inversion injuries when landed upon.

That feature together with the absence of warnings relating to it was – she ruled – a “safety defect” as defined in the Australian Consumer Law.

She also observed that that the manufacturer’s promotional material – which included phrases such as “jump safely to the edge” and “no hard edges” – contributed to users being entitled to expect a higher degree of safety.

The court held that a clear and visible warning at the trampoline entry could have drawn users’ attention to the risk associated with landing near the cleats.

Had such a warning been provided – she reasoned – Forostenko would likely have exercised greater caution, potentially avoiding the injury. She awarded him $744,175 in damages.

Springfree appealed solely on causation, contending that the trial judge had applied the wrong test in determining whether the injury was suffered “because of the safety defect” under ACL section 138(1)(c).

Appeal judges Bond JA (with whom Boddice JA and Davis J agreed) had to decide if the absence of a warning was a necessary condition of the injury.

In their view, causation under section 138 ACL required the application of the ‘but for’ test and the plaintiff to prove, on the balance of probabilities, that but for the defendant’s actionable conduct — in this case, the absence of a proper warning — the injury would not have occurred.

The plaintiff thus had the evidentiary burden of establishing the counterfactual — that had the warning been given, the injury would probably have been avoided.

Mere proof that the product carried an elevated risk or that the manufacturer failed to give adequate warnings was insufficient – in a failure to warn case – in the absence of evidence that the plaintiff would have acted differently in response to such warnings.

Justice Bond found that the trial judge had effectively reversed the burden of proof. Rather than requiring the plaintiff to establish that he would have read and acted upon a warning, the primary judgment rested on the absence of any reason to conclude that a warning would have influenced his behaviour. This was an incorrect application of the causation test.

There was – in his view – no sufficient basis to infer that Forostenko would have read or acted on any warning. His entry onto the trampoline was held to be spontaneous and impulsive. Further, he had a history of engaging in recreational activities involving risk without consulting warnings or safety instructions.

In these circumstances, the court held it was not open to find that a warning would probably have prevented the injury.

It also concluded that the alternative negligence claim failed. Civil Liability Act section 11 also required the plaintiff establish factual causation by proving that the alleged breach of duty was a necessary condition of the harm suffered.

The failure to prove the relevant counterfactual proposition thus defeated both claims.

The court allowed the appeal, set aside the trial judgment, and entered judgment for Springfree, with costs.

Had the case been pleaded differently – simply on the basis of an resulting from a defective product – i.e. with no “failure to warn” element, the result may have been very different.

Categories: defective products , sport injury